Inside the Skip Holtz era of UConn football

Before UConn moved up to FBS (formerly Division 1-A), Holtz took the program to another level in the final FCS (1-AA) years.

Everything that UConn football has become in the 21st century began in the waning weeks of 1993. Every ounce of gridiron exuberance and frustration that Husky fans have experienced over the past thirty years grew out of the ambitions of an athletic director.

Lew Perkins wanted to establish another signature program in Storrs. The path forward began with a famous last name. Louis Leo “Skip” Holtz was no longer just the son of the country’s most recognizable college football coach, as he was when Perkins introduced him to the Nutmeg State in December 1993. In Storrs, he became a bona fide program builder, leading UConn to its first-ever Division I-AA playoff appearance in 1998. Two seasons later, in 2000, the Huskies joined Division I-A, the forerunner of today’s Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS).

By the time Skip left to join his father Lou Holtz’s staff at the University of South Carolina, everyone involved in the Connecticut football program knew they were doing things the Division I way. They played like a D-I team, recruited like one, and presented themselves as the state’s flagship program.

“Everything we did was Division I besides our schedule. The path was already there,” wide receiver Carl Bond said of the Skip Holtz Era (1994-1998). Bond starred at Hamden Hall before becoming one of Holtz’s first signees in Storrs. The West Haven native went on to become a Division I-AA All-American. He enjoyed a long career in professional football, playing primarily in the Arena League.

The end of an era (and the start of a new one)

The modern era of UConn football began with what has come to be known euphemistically as a coach and his institution “parting ways.”

Tom Jackson resigned as the University of Connecticut’s football coach on November 17, 1993, just days after the completion of a 6-5 season. His contract was set to expire, and Perkins had no plans to renew him. Jackson spent 11 largely successful seasons as the head coach in Storrs, compiling a 62-57 overall record. His best years came in the home stretch of the 1980s, when he posted five consecutive winning seasons from 1986 to 1990. The Huskies won a piece of three Yankee Conference titles (1983, 1986, 1989) but never earned a bid to the Division I-AA football playoffs, a creation of the great schism of college football’s top division in 1978.

Things had soured of late. UConn finished below .500 in 1991 and 1992 before making a slight return to form in 1993. Everything about the program, though, seemed stuck. They played a ground-and-pound style of football increasingly at odds with the more wide-open systems being adopted elsewhere in their conference. Tom Jackson’s teams threw the ball infrequently and relied on a narrow recruiting base that consisted largely of southern New England and upstate New York.

“It was a very blue-collar, tough brand of football. They always played great defense and were going to run the ball down your throat,” linebacker Brad Keatley, who redshirted as a freshman during the 1993 season, said of Tom Jackson’s teams.

Carl Bond didn’t register UConn on his radar as he drew the attention of football scouts far and wide in the early 1990s at Hamden Hall.

“I was not interested in UConn football as a kid,” Bond said. “As a kid, you think you’re going to the biggest of the biggest.”

And, despite UConn’s success under Jackson, there was nothing that seemed particularly big or aspirational about UConn football.

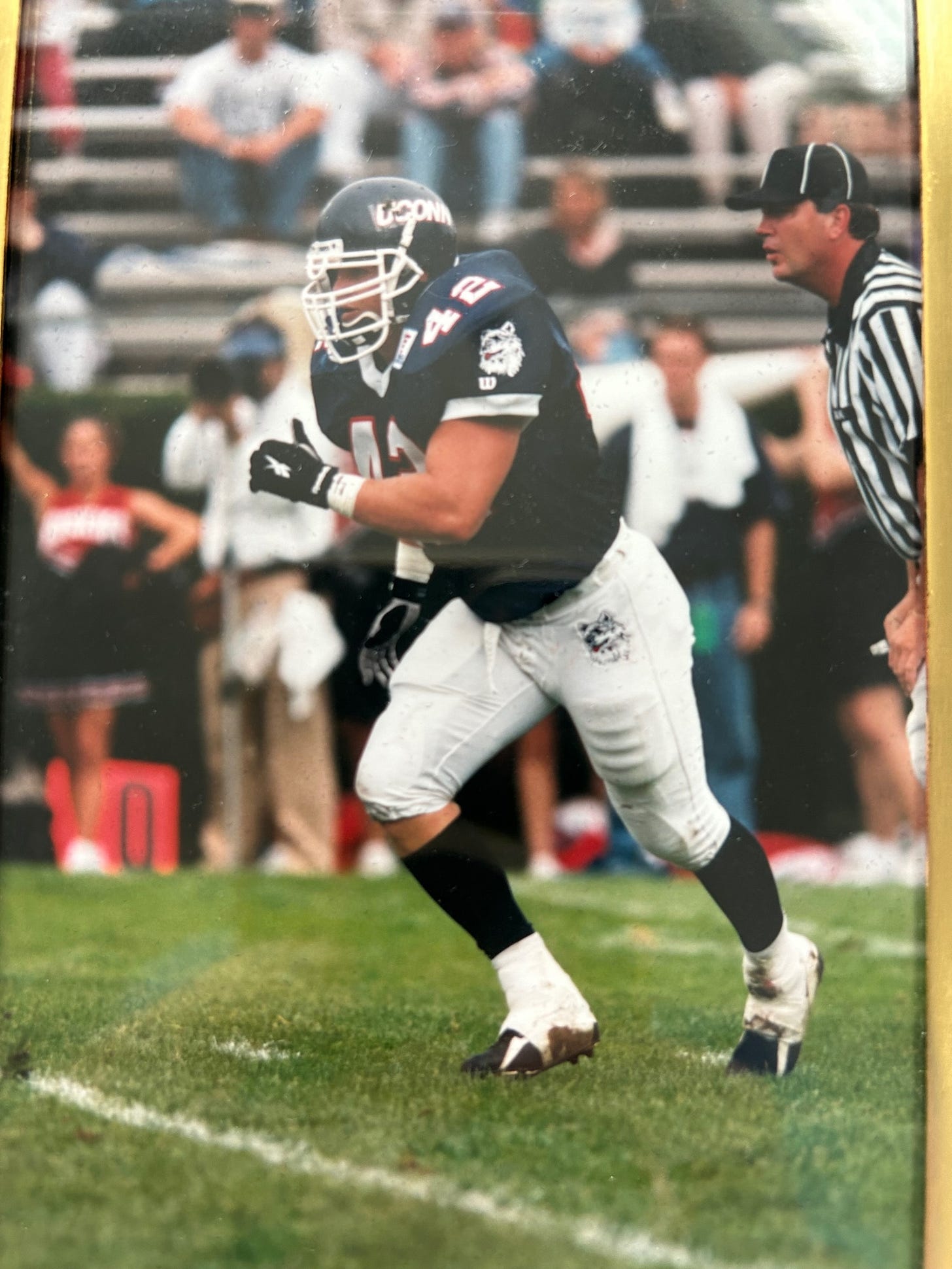

“I liked Coach Jackson a lot as a person,” defensive lineman Ryan Coutant said. Coutant, a powerhouse tackle for the Huskies, started as a freshman on Jackson’s last team. He had not played football until his senior year of high school but excelled under future Boston College coach Steve Addazio at prep power Cheshire Academy. Addazio made sure that coaches across the Yankee Conference took notice of Coutant, but he chose UConn. “All the players liked him [Jackson] and I thought he was a good coach. It seems like the state of Connecticut was wanting to launch the program on another level.”

Perkins had been pushing for UConn’s evolution into a Division I-A program and inclusion in the Big East football conference. Warren “Moose” Koegel, UConn’s recruiting coordinator, made UConn’s eventual move to the Big East a staple of his pitch to prospective players. Talk of the New England Patriots relocating to Connecticut and possibly sharing a stadium with a newly Division I UConn football program turned eventually into formal commitments from the state government. All of these great expectations fueled the idea that the Huskies needed to do something to break out of their status as a solid if unspectacular Division I-AA program.

That something proved to be hiring Skip Holtz. After a month-long search, Perkins tapped the youthful Notre Dame offensive coordinator to be Connecticut’s new head football coach. Then 29 years old, Holtz became the face and force behind a series of significant investments in the school’s football program. Perkins interviewed close to a dozen candidates, including two that went on to be among the highest profile head coaches of their era: then-Michigan offensive line coach Les Miles and Virginia offensive coordinator Tom O’Brien.

Skip Holtz had been on the staff of his legendary father, Lou Holtz, for the past four seasons at the University of Notre Dame. He served as offensive coordinator on the Irish’s 1992 and 1993 clubs, both of whom won the Cotton Bowl. The ’92 Irish finished fourth in the final polls. The ’93 Irish finished second and should probably have been national champions, having defeated eventual No. 1 Florida State and finishing with the same overall record. Rather than giving Notre Dame a second title under Holtz, the pollsters decided it was time for Bobby Bowden, the Susan Lucci of college football, to finally get his championship.

Holtz had overseen the Irish’s conservative though pro-style offense, which pummeled opponents on the ground with the likes of Reggie Brooks, Jerome Bettis, and Lee Becton while enabling quarterbacks Rick Mirer and Kevin McDougall to gut opposing defenses off the play action pass. He would bring a modern, streamlined approach to the game with him that seemed simultaneously new and old.

Raising the standards

Perkins brought in Holtz with visions of revolutionizing the program. He was to be Perkins’ signature hire, just as his predecessor John Toner began the transformation of the men’s and women’s basketball programs into major powers with the hires of Jim Calhoun and Geno Auriemma respectively.

Coaching in Storrs was a homecoming of sorts for Holtz. He was born at Windham Hospital in Willimantic in 1964 soon after his father took an assistant’s job at UConn under Rick Forzano. Forzano lasted two middling seasons at UConn before moving on to a position with the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals. Lou Holtz secured a position at the University of South Carolina and moved his family to Columbia. This would be the first of six coaching-related moves that the Holtz family made during Skip’s childhood.

Adjusting to radical changes was par for the course with the Holtz family. It didn’t take the returning players long to realize how radically different things were going to be under Skip Holtz.

“It was a pretty big change. There was more of an emphasis on team with Skip, being brothers. He really changed the mindset,” Keatley said.

“Winter workouts started at five or six in the morning. It was boot camp-style drills. It was mentally and physically tough and it was great. It brought us together as a team,” Matt Feschak, a rugged fullback whom Holtz recruited out of Northeast Ohio, said.

Under Tom Jackson, most players went home for the summer and worked out on their own. During Holtz’s tenure, the vast majority of players stayed on campus and completed rigorous workout programs that were overseen by the team’s strength and conditioning coach, a position that had not existed during the previous regime. The players had a brand-new weight room, a space that had formerly been the visitor’s locker room at Memorial Stadium.

“With Tom Jackson, football season was football season. With Skip, it became a year-round thing. We were together constantly. The camaraderie was really built around teammate and brother. We were really working at it as a team,” Keatley said.

“He [Holtz] held everyone accountable. He let you know when you did well and when you didn’t,” Bond said. “He balanced when to be rah-rah and when to be the calm motivator. There were times where he turned it up. He was able to time that well. Sometimes, it was ‘this is what it’s like and this is what we’re going to do. If you’re not ready to do that, go walk out that door.’”

During the season, practices lasted two hours and were broken down into five-minute periods, adopting an approach that Notre Dame and other top programs had recently implemented.

“Practice was always very structured and there was never any confusion about what you were going to be doing,” Feschak said.

“If we didn’t have it right, we’d start that clock over,” Bond said.

“I think Skip Holtz was more hands-on working with his coordinators while Tom Jackson was more of a general who took a higher-level view of things,” Coutant said.

“There was an increase in intensity in practice,” according to Keatley. “When Skip came, I remember having epic battles of the offense and defense going at it. It was not uncommon for fights to break out. There were more one-on-one drills and competitive drills. Starting offense against starting defense. With Tom Jackson, offense and defense were split up more. With Skip, it was about getting us to compete on every single rep.”

In a more general sense, the culture of the UConn football program changed too. The program presented itself to its community and its state in a very different fashion.

“Everything upgraded. Your uniforms. Your gear. The facilities. All of a sudden, I’m seeing billboards driving home promoting UConn football,” Coutant said.

“Under Tom Jackson, the football team had a bit of a reputation and not in the best way. Skip gave the media guide to the bars and said ‘if you see one of these guys come in here, you tell me.’ We quit doing the bar scene when Skip came in,” Keatley said. “They would send coaches routinely to classes to make sure we showed up and if your position coach was at a class that you did not show up for that day, you were going to be running the rest of that week at 5 AM.” Under Holtz, players were expected to attend study hall and work closely with academic advisors.

Despite the stringent expectations, the guys on the team generally regarded Holtz as a player’s coach.

“[Coach Holtz] was jovial. He always had a smile on his face. He was an extremely positive guy. He was more of a player’s coach. He took a lot of time to get to know players and had players to his house for dinner,” Coutant said, quite the opposite of the fiery Addazio he encountered at Cheshire Academy. He notes that Tom Jackson was also more of a player’s coach who chatted casually with players during warmups.

Showing it on the field

Schedule-wise, the 1994 season did not bode well. Four of their Yankee Conference rivals entered the season nationally ranked. All three of their non-conference foes were also ranked, including their first two opponents. UConn would host Nicholls State (Louisiana) and Troy State (Alabama [now one of the best G5 programs in the FBS]) to start the season. Moreover, many of UConn’s top performers in 1993 had been seniors. 1994 looked to be a rebuilding year, regardless of the big-name coach now leading the program.

Tough schedule or not, Holtz developed a mantra of “Don’t Flinch” in his first season in Storrs, a phrase that concisely articulated the winning culture he planned on bringing to town. UConn hung tough against Nicholls and Troy but ended up on the short end against those I-AA powers. Existing footage of both games shows UConn to be a self-assured bunch. UConn took to the field in uniforms reminiscent of the Bill Parcells-era New York Giants. They competed with a confidence that looked and sounded like variations on such 1980s Big Blue icons as Mark Bavaro, Lawrence Taylor, and Leonard Marshall. As the defense took to the field, players on the sideline yelled “three and out” to make clear the unit’s purpose.

The Troy State game was UConn’s first night game since 1989 and drew an overflow crowd of more than 13,000 to Memorial Stadium. Hours before kickoff, a vibrant tailgate scene took hold on campus, which became the norm during the Holtz era.

“I remember my freshman year, my high school in upstate New York had more people going to them than went to UConn football games,” Keatley said of the feel of Huskies home games before Holtz and night football, when crowds of 10, 15, and even 18,000 attended games during the second half of the 1990s.

“It was a different campus when we had night games. It was electric. A great experience,” Bond said.

In game three, the Huskies snagged their first win, upending Richmond behind a 136-yard rushing performance from Ed Long, a rugged ball carrier who embodied the old-school, grind-it-out football that had been UConn’s historic signature. Long broke the Huskies’ career rushing record that evening but ended up missing much of his senior season with injuries. For the remainder of the season, UConn relied on a big, physical back named Wilbur Gilliard who proved himself to be a similarly effective rusher, crossing the 1,000-yard threshold in the season finale.

Playing with Tom Jackson’s personnel, UConn remained a ground-and-pound team in 1994 and fought its way to a 4-4 mark in the Yankee Conference. Despite a 4-7 overall mark, UConn made virtually every game interesting. All but one of their 1994 contests were competitive into the fourth quarter.

As usual, UConn finished near the top of the league in most defensive categories. Defensive captain and four-year-starting linebacker Paul Zenkert was among the leading tacklers at the I-AA level and earned all-conference honors. Excellent special teams became an immediate Holtz hallmark. The Huskies blocked and returned three punts for touchdowns in 1994.

The 1994 Huskies drew more than 71,000 fans to six home games, a program record and third-best in the Yankee Conference. Connecticut finished ninth in attendance the previous season and lured half as many spectators.

Now a battle-tested team, UConn headed into the 1995 season as a more cohesive unit, one that was to be bolstered by the significant additions being made to its roster and coaching staff.

“As the momentum started to build around moving to the Big East, they were able to attract more and more guys that were those in-betweeners. I remember hearing that some of these guys coming in had offers from bigger schools,” Keatley said. UConn stocked up on speed at the skill positions and on defense. Holtz sought to bring more balance to the UConn attack. He found a strong-armed quarterback capable of stretching the field in Shane Stafford, who hailed from Berks County, Pennsylvania, not a typical recruiting area for Huskies football. In addition to the explosive Carl Bond, UConn signed running back Tory Taylor from Winter Garden, Florida and wide receiver John Fitzsimmons from Bishop Feehan in Attleboro, Massachusetts. All four would go on to fill up the offensive record books at Connecticut.

“Shane Stafford was a great quarterback and a great leader. The kind of guy who was first in every drill and led by example,” Matt Feschak, a classmate of Stafford’s, said. Stafford started at quarterback as a freshman in 1995 and proved an immediate spark to the offense, throwing for nearly 500 more passing yards than his predecessor, the highly respected Zeke Rodgers. Over the next three seasons, Stafford rewrote the UConn offensive record book.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The UConn Fast Break to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.